|

|

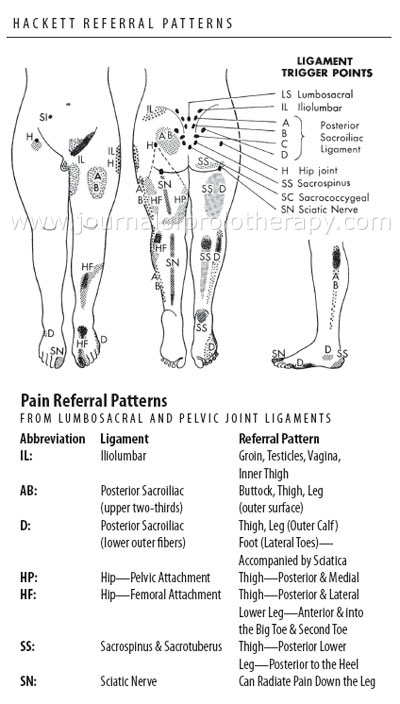

Dear Colleagues: "Sciatica" (like "allergy" or "arthritis") is one of those so-often misused semi-medical terms that has now become close to meaningless. Whenever the word comes up, the physician needs to ask clarifying questions: How was the diagnosis made? Who made it? Where exactly is the pain? etc. For lay people sciatica simply means pain down the leg. Often the pain is not even down the back of the leg i.e. does not follow sciatic nerve distribution. Sadly physicians sometimes misuse the term "sciatica" also. Whether this is due to ignorance or laziness, I cannot say. In any case physicians should probably abandon the word because of the many misunderstandings that surround it. We don't have a special word for describing cervical or thoracic nerve root pain, so why do we need one for the leg? To be fair, leg pain caused by nerve root irritation is not always simple to diagnose. Sciatic nerve irritation is rare and usually caused by piriformis muscle spasm. (See Volume 1, No. 3 in the newsletter archive.) Irritation of lumbar and sacral nerve roots is more common, but probably much less common than generally believed. One on-line medical dictionary described sciatica as: "Pain in the lower back and hip radiating down the back of the thigh into the leg, initially attributed to sciatic nerve dysfunction (hence the term), but now known to usually be due to herniated lumbar disk compressing a nerve root, most commonly the L5 or S1 root." I disagree. Orthopaedic physicians with whom I have discussed this subject estimate that only 3 to 5% of patients with leg pain actually have nerve root irritation. The rest have mostly referred pain from ligaments or muscles, or pain related to autonomic nervous system dysfunction (the extreme manifestation being sympathetic dystrophy). In this short newsletter, I will not attempt to discuss the many methods of diagnosing nerve root irritation, but will rather concentrate on the information that can be obtained from knowledge of referred pain patterns. There are two "bibles" to consult: The first is George Hackett's book "Ligament and Tendon Relaxation (Skeletal Disability): Treated By Prolotherapy". The second is Travel and Simon's "Myofascial Pain and Dysfunction: The Trigger Point Manual". Hackett's is the more valuable for this differentiation, primarily because of his maps of pain patterns in the legs arising from low back structures, especially the ligaments. He demonstrated that posterior leg pain could be caused by ligament irritation (He believed it to be "laxity".) However referred pain always "skips" the posterior knee. When no pain is felt behind the knee, one can be certain that the sciatic nerve or one of its nerve roots is not involved. The other useful distinction is heel pain. If pain is felt under the heel, it is referred from a sacrospinus or sacrotuberus ligament. This is commonly misdiagnosed as "plantar fasciitis". If the pain "grips" the heel, it is of sciatic nerve origin.  How does the neural therapist use this information? If the patient has nerve root irritation, caudal epidural injections of up to 50 ml procaine ½% can be helpful. No steroid is required. (This technique was discovered independently of the neural therapy world by the British orthopaedic physician James Cyriax in the 1950s.) If the pain is not of nerve or nerve root origin, the usual search for interference fields and/or somatic dysfunction should be undertaken. This is where at least some knowledge of both neural therapy and osteopathy (or other systems of biomechanics) can be so useful. It is not unusual to find both mechanical and non-mechanical interference fields contributing to a leg pain syndrome. Here is an example: A 49-year-old man presented with right leg pain of three week's duration. The pain did not follow any pattern suggesting nerve irritation and was associated with low back stiffness. The pain had begun soon after a yoga session where he felt he had strained himself performing a back extension exercise while lying prone. He also felt at the time mild discomfort in the region of a left inguinal hernia surgical scar, where he had undergone surgery a few months before. On examination, there was mild hamstring tightness on the right side. While lying supine the pelvis was asymmetric with the right innominate rotated anteriorly. While prone, the sacrum was rotated anteriorly on a left oblique axis. Paraspinal muscle tension could be felt on the right side of the lumbar spine. Autonomic response testing detected an interference field in the left inguinal scar. This was treated with the Tenscam device. (Infiltration with dilute procaine would have been an equally effective alternative.) There was an immediate restoration of pelvic symmetry and muscle balance and the leg pain resolved. It is time for physicians to discard the word "sciatica", and learn to diagnose leg pain properly. Proper diagnosis leads to correct treatment. Should we be satisfied with less? ------------------------ The 6th World Biennial Conference on Neural Therapy was held in Ecuador on March 20-23rd. Carlos Chiriboga reports on some highlights:

------------------------ Sincerely, Robert F. Kidd, MD, CM |