|

|

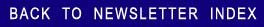

Dear Colleagues: I recently attended an osteopathic manipulative workshop - a brain-stretcher in more ways than one. It was a three‐day course sponsored by the American Academy of Osteopathy, taught by Bruno Chikly, MD, DO and entitled "Palpating and treating the brain, brain nuclei, white matter and spinal cord". This might sound far removed from anything to do with neural therapy, but I picked up some ideas that I believe are worth sharing. I have often written about the similarity between interference fields and what osteopaths call "somatic dysfunction". Both are focal areas of dysfunction; both can create disturbance locally or remotely; and in both the autonomic nervous system plays a prominent role. A knee scar might cause pain in the knee or in a shoulder. A somatic dysfunction of a sacroiliac joint might cause pain in the low back or a headache. Cranial osteopathy is a unique discipline in that it includes the mechanics of the cranial bones and the attached soft tissues as well as the rest of the musculoskeletal system. Dr. Chikly carries cranial osteopathy a step further by incorporating the contents of the cranium and spinal cord, even those structures with no mechanical attachment to the cranial bowl. For example he will speak of somatic dysfunction of a lobe of the cerebellum, of a nucleus of the thalamus or even of a basal nucleus. How can this be? Even if these things exist, how can they be diagnosed, let alone treated? The answer seems to lie in "tuning in" to intrinsic rhythms of the brain.Cranial osteopaths use this technique by "tuning in" to the primary respiratory rhythm, a slow, wave-like "opening and closing" of the whole body at about 10 to 14 cycles/minute. Other fluctuations exist, such as the Traube‐Herring oscillation, supposedly mediated by the sympathetic nervous system. Chikly tunes into one of these in the brain (the "universal rhythm") at about 2 or 3 cycles per minute. In one phase one hemicranium rotates anteriorly on a horizontal axis while the opposite side rotates posteriorly. At the end of each phase there is a pause of a few seconds before each hemicranium rotates in the opposite direction. "Tuning in" and "balancing" this movement down‐regulates the autonomic nervous system and prepares it for the next step. The next step is to identify somatic dysfunction of specific structures within the brain. ("Somatic dysfunction" here could just as well be termed "interference field".) In one basic technique, the operator places his or her thumbs about one inch apart on each side of the sagittal suture of the supine patient just anterior to the coronal suture. The touch should be very light, while the operator concentrates his or her "mind's eye" on the different layers of the brain from superficial to deep, feeling for the presence of a disturbance at each level. With the thumbs positioned as described above, one passes through the cerebral longitudinal fissure to the Indusium Grisium, a thin later of grey matter covering the superior surface of the Corpus Callosum. The Corpus Callosum has both medial/lateral and longitudinal striae and both directions should be tested for tension in the tissues. (Repositioning of the fingers is required for testing the longitudinal striae.) Going deeper still, below the Corpus Callosum are the two lateral ventricles separated by the Septum Pellucidum. The Septum Pellucidum attaches inferiorly to the Fornix. (Again some change in position of the fingers is necessary to evaluate these structures.) Similar techniques are used to assess the thalamic nuclei, the hypothalamic nuclei, the basal ganglia, the brain stem nuclei, cerebellum, etc. I came home from this course somewhat overwhelmed by the anatomy that I needed to (re)learn. However even a little knowledge raises possibilities and soon after returning to my office I saw a 56‐year old woman with right sided Parkinson's tremor and muscular rigidity. She had been diagnosed with Lyme disease a few months before and was responding nicely to treatment. However she had a most distressingright buttock and posterior leg pain that had not responded to any treatment, including osteopathic manipulation. Because she also had panhypopituitarism, (common in Lyme disease) I decided to assess her pituitary gland. In fact a somatic dysfunction was found and I treated it. Within minutes her leg pain disappeared and it has returned only partially in the last two months. So what does this have to do with neural therapy? Interference fields within the brain no doubt exist, but classical neural therapy does not have the tools to diagnose or treat them (other than the "crown of thorns" and perhaps injection of cranial and/or cervical autonomic ganglia). This is where an energetic model of neural therapy may come into its own. If an interference field is looked upon as a disturbance of the body's energetic field, energetic methods of diagnosis and treatment may provide answers that procaine injections cannot. The manual skills needed to practice Dr. Chikly's method are demanding and likely possible only for high-level osteopaths. However other tools exist for assessing intracranial structures, including homeopathic testing vials with "signatures" for each cranial structure. Scalp and ear acupuncture may also provide avenues for treating specific intracranial interference fields. Below are two pictures (kindly shared by Dr. Chikly) showing how intracranial structures can be moved using osteopathic "energetic" techniques. This 2-year old child with nystagmus, headaches and insomnia, (requiring codeine to sleep each night) was cured of headache and slept normally after one treatment. Although not equal cuts, the shift in the sagittal sulcus is obvious.  I have always considered neurology to be an intellectually stimulating but therapeutically depressing medical specialty. This is especially true when the only treatment options are drugs or surgery, but it seems that times are changing. Neural therapy (in its broadest sense) may have diagnostic and treatment possibilities in the central nervous system that we could not have imagined only a short time ago.

I have always considered neurology to be an intellectually stimulating but therapeutically depressing medical specialty. This is especially true when the only treatment options are drugs or surgery, but it seems that times are changing. Neural therapy (in its broadest sense) may have diagnostic and treatment possibilities in the central nervous system that we could not have imagined only a short time ago.Sincerely, Robert F. Kidd, MD, CM |